2017 GoGriz.com Person of the Year

12/25/2017 6:49:00 AM | Softball

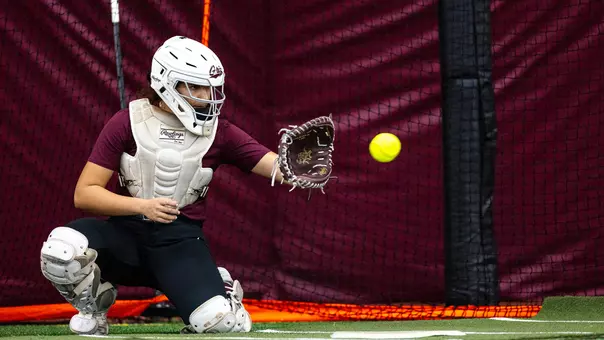

Colleen Driscoll pitched last season with an orange ribbon in her hair and a pair of broken titanium rods in her back.

What did you see when she stood inside the circle, which she did 25 times last spring, when Montana was winning a Big Sky Conference championship? Just another loaded arm on a staff of them, which the Grizzlies rode to the NCAAs?

Did you recognize the ribbon on the days she pitched? Or know what it represents or the weight it carries? How it connects her to a tragedy that took place in 2009? And no matter how badly she'd like to lose the hurt, how she never wants to forget that June day or lose the connection to her brother?

Did you know about the hardware, 23 pieces in all, that she pitched with, a titanium scaffolding that encased her spine from the base of her back to the base of her neck? Or how the most important pieces, the rods that paralleled her backbone, had both snapped in two more than a year earlier?

You saw a sophomore pitcher who became an NCAA tournament team's No. 2 starter. Who finished the season with an ERA of 2.98, the sixth-best average in the Big Sky.

What you probably didn't see was the orange ribbon, a game-day symbol of perseverance and remembrance. Or know about the broken rods in an already compromised back, or how a system of hooks and screws, installed to free her from Scheuermann's kyphosis, had become a millstone.

Or realize the strength it took for Colleen Driscoll simply to make it through each day, much less emerge as a key player on a championship team.

"Hands down the most mentally tough, determined person I've ever coached, and it's not even close," says former Montana coach Jamie Pinkerton, now at Iowa State, who's been coaching at the Division I level for more than two decades.

There is not a written set of criteria that is used when determining the GoGriz.com Person of the Year, which is being handed out for the third time this Christmas.

The award's first two recipients -- Emily Mendoza and Jessica Bailey -- were both recognized for the work they did for others, both going on service trips to Africa as part of their undergraduate experience and education.

Colleen Driscoll is this year's honoree and is not at all like Mendoza and Bailey, at least for the reason she is this year's recipient. While Mendoza and Bailey were chosen for the things they did for others, Driscoll is the 2017 GoGriz.com Person of the Year for what she's done just to get herself to this point.

"I've never heard of anything like she's gone through," says Pinkerton. "I would understand if the kid threw her hands up and said, I've had enough. I can't handle this anymore. But she never has. That's why she's one of the most special players I've ever had the privilege of coaching."

The question, then, becomes this: Have the circumstances of Colleen Driscoll's life made her the person she is -- strong, resilient, tough, unbreakable, a new descriptor for each new hurdle cleared -- or was she that person from the start, uniquely prepared to handle every new obstacle placed before her?

Did bending over to put on a pair of socks her freshman year at Montana and feeling a pop in her back -- not knowing two titanium rods, placed a year and a half earlier and thought to be indestructible, there for life, had just broken -- make her stronger?

Or was she already a driven athlete, who assumed the pain that washed over her that day was just her body continuing to adapt post-surgery and followed through with that day's weight-room workout without giving it a second thought?

What about the complications from the surgery she underwent the August before her senior year at Mountain View High in Vancouver, Washington, when things spiraled out of control, when there were fears of paralysis and later the onset of an infection that led to her being quarantined?

Or the news she received as an eighth grader, when a doctor told the Driscolls that it wasn't the poor posture of a lazy teenager that was afflicting their daughter, it was Scheuermann's and that she would one day need back surgery?

Or two years before that, as a sixth grader, when her school was put into emergency lockdown, when she was escorted by security out of her classroom and taken to her dad, who she saw crying for the first time in her life, who had to break the news to her about her brother and best friend?

Did all those experiences make the girl, or was Driscoll just born with it, provided with all she'd need from the start to handle everything that was going to be thrown her way?

"She had that as a 4-year-old," says Scott Driscoll, Colleen's dad. "I wish I had a tenth of what she has from that standpoint."

The Driscolls were a foursome before Colleen arrived, with Scott working in computer software in Portland, Kelly in finance at Nike in Beaverton.

With Kaylyn and Quinn already in the mix, kid No. 3 tipped the balance. It could no longer be one-to-one supervision when it came to youth sports. And since Colleen was always tagging along anyway, watching everything, processing, taking it all in, she might as well be put in tee-ball to see how she did.

"Even at that age she was an amazing observer of the games when her older siblings were playing," says Scott. "When she finally got on the field, it was like she had been playing for years, even though she was just a little kid."

See Quinn, a year and a half older than Colleen, but the two often together on the same age-group teams, looking so much alike and chumming like besties that people assumed they were twins.

And see the Johnson family, whose three children matched up in age perfectly with the Driscolls: the older sisters, then Ryan and Quinn, then Kendall and Colleen, all of them being pulled toward sports, none more so than Quinn, who by the eighth grade was emerging as a three-sport standout.

So no one would have thought anything of it that June day in 2009, not long before school would be out for the summer, the final step before Quinn could enter high school and play football, basketball and baseball at a higher, more competitive level, when he was racing around the track in PE class.

All of it -- his potential, his future, his talent -- was on display as he made his way around the final lap of the one-mile race, still enough remaining in the tank that he could be heard urging on his classmates.

But the very thing that was the engine of it all, his heart, gave in, no longer able to power Quinn's dreams. He fell to the track, a victim of sudden cardiac arrest. What no one could have known or would have guessed was that he was a victim of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The school was placed in a medical lockdown. Teachers and emergency responders tried to revive Quinn. Security was sent to find Colleen. "They just told me my brother fell," she says.

She was brought to the front of the school. That's odd, she thought, why is my dad here? "I'd never seen him cry before, so I knew something was wrong." Quinn did not survive. Colleen had lost her best friend. A family was faced with a tragedy.

Another question: Did Colleen gain strength from the rest of her family in the days that followed, or was it the other way around? Or was it a collective effort to support one another as they moved on, all wanting to do something that would make sure Quinn would never be forgotten?

"Colleen was presented with two paths," says Scott. "You can either give up and let people feel sorry for you or you can go out and do things with even more purpose, like I'm going to dedicate this to my brother. That's what she was thinking."

The family as well, who quickly set up the Quinn Driscoll Foundation, because they didn't want another family to have to go through what they'd just experienced. Instead of closing in as a family, they opened up and shared Quinn's story, balancing the suffering with the good they wanted to come out of it.

"You can have a tragedy like that and say how horrible it was that we lost our 13-year-old son, or you can do something about it and try to turn tragedy into something positive," Scott says.

Today the foundation has two goals: the education and screening of youth for issues associated with sudden cardiac arrest and the distribution of automated external defibrillators.

Would a screening have saved Quinn's life? No one knows for certain, but it very likely could have. The foundation isn't keeping track of potential lives saved through its work and outreach. There was the first, way back when, one family spared the heartache, and that was enough for the Driscolls.

"If we help one family, if we help one kid, we've done our job. That was kind of our motto from the start and still is. We kind of stopped counting at one save," says Scott.

The foundation is based in Vancouver, but its reach has extended to Missoula, in more ways than Quinn's younger sister pitching for the Grizzlies. Step inside the indoor hitting facility behind Grizzly Softball Field and you'll find an AED, courtesy of the Quinn Driscoll Foundation.

"It's not only there for the players who use that facility but for the hundreds and even thousands of people who are out there on an annual basis. To have that life-saving device is what it's all about," says Scott.

Because of the AED, Quinn Driscoll has a permanent presence at Grizzly Softball Field. He might also come to mind, from now on, when Colleen Driscoll steps out of the dugout and walks toward the circle sporting her own game-day memorial. His presence will be all around.

"Orange was Quinn's favorite color. He dreamed of playing college baseball and never got the opportunity. I get it for both of us," says Driscoll, who has had postural issues dating back to her early years.

If scoliosis is an S bend of the spine when looking at someone from behind, Scheuermann's presents itself as a C when looking from the side. Vertebrae grow unevenly, which leads to abnormally excessive curvature.

When nobody knew that Driscoll had Scheuermann's, everyone just assumed she needed to be told how to carry herself. "My parents would yell at me to stand up straight. They figured I had bad posture, but I couldn't straighten up," Driscoll says.

It wasn't until the eighth grade that she was finally diagnosed. It was more of an aha moment than alarming news. It explained a lot and came with a prediction that she would probably need surgery at some point, years and years down the road.

At least it wasn't going to hold her back now, when she had so much she wanted to accomplish. And didn't years and years down the road sounds like another lifetime to an eighth grader, something she might need to address as an adult? At least it wasn't going to affect her childhood, thank goodness.

"Surgery was never in question. My doctor said that was a last resort," says Driscoll.

The ACL tear she suffered in eighth grade playing basketball put an end to the promise she showed in that sport. She played volleyball as a sophomore and junior, once her knee had healed, but it became mostly about softball, first in high school and club, then with a goal of playing it in college.

She was good enough that she caught the eye of Montana's coaches, who were in the process of starting a program.

"What we really liked was that she was a tall, strong individual with good fundamentals," said then pitching coach and now head coach Melanie Meuchel. There were concerns but only because the coaches didn't know the entire story.

"She always had her shoulders down and her head down. She competed and was into what she was doing, but it felt like there might be a confidence issue. You just wanted her to be a little more confident and put her shoulders up. Little did we know."

And little did Driscoll know about the next trial that was coming her way. In the spring of her junior year she saw her doctor for her annual exam. She expected it to be routine, to be told the same thing, that there was nothing to be concerned about at this point. To keep on doing what she was doing.

What she heard turned her world upside down. She had faced a life-changing event as a sister years before. Now she was forced to do it again as a softball player, facing her mortality as an athlete.

"The doctor came in and said, I think you need surgery," Driscoll recalls. "I was like, What? It's hard at 17 to accept that your dreams of playing college softball are literally over in a 20-minute doctor's visit."

The effects of Scheuermann's were advancing faster than anyone had anticipated. The degree of curvature of her spine had gone beyond what was considered safe. If it wasn't corrected, it was going to start affecting her health.

Sections of her spine where vertebrae had formed like wedges would need to be broken, straightened and fused back together. Bracketing it all together would be the 23 pieces of titanium, including the two rods that would extend from her T3 to her L2, in other words from top to bottom.

It didn't need to be an emergency surgery but it had to happen sooner than anyone wanted.

The decision she had to make was, when would she undergo the procedure? Finish out her senior season in high school, then go under the knife? But she wanted to go to college too and not put that on hold. And what about playing softball in college? And going to physical therapy school after that?

Since the recovery would require some down time, followed by extensive physical therapy, there was no good answer. Well, there was, but Driscoll wasn't ready to think about it. Was she prepared to sacrifice her senior season playing for the Thunder? Was she ready to admit her softball career might be over?

"He recommended doing it while I was young, so I could recover at home. There is no good time in college to do that, so I had to look at life in a bigger picture," says Driscoll, who also knew she had to contact the coaches of the schools that were interested in her and tell them the news.

That meant reaching out to Montana, which had become her No. 1 school, thanks to family friend Ryan Johnson, who ended up playing football for the Grizzlies. The defensive end was third-team All-Big Sky Conference in 2016 as a fifth-year senior.

The Johnsons were the ones who let the Driscolls know Montana was starting a softball program. It only took one visit to Missoula to watch one of Johnson's football games for Driscoll to discover the school of her dreams.

"I fell in love with it, and that was my biggest thing. I wanted to find a school I loved no matter what, whether I was playing softball or not," says Driscoll.

She decided to schedule the surgery for August, before the start of her senior year. Because there were no guarantees she would ever play softball again, it gave the final games of her junior season at Mountain View and her club team's tournaments that summer the feel of a possible farewell tour.

Was she making the final start of her career? Of her life? Had she just thrown her final curveball? Had she just had an in-game meeting with her catcher for the final time? Had she just taken her final bus trip with teammates who would be friends for life? What was out there that could ever replace this?

Wanting to extend the dream as long as possible, she waited until the day before her surgery to finally break the news to Montana's coaches. Her message: Thanks but you should probably move on. It was a disappointment felt on both sides.

"She let us know she had to undergo a procedure and didn't know if she'd ever play softball again," says Meuchel. "She said she appreciated us watching and following her but feel free to move on with the recruiting process. It was a bummer. We thought this kid had a chance."

The procedure wasn't necessarily going to be the end of her pitching career, but she knew she needed to prepare herself for the possibility. Just like she knew she needed to be ready for the long haul. Her doctor warned her the recovery from the surgery could take up to 12 months.

That was if everything went according to plan, which it didn't. During the surgery the dura mater enveloping her spinal cord was cut. Fluid leaked, leading to painful spinal headaches. And she had no feeling on her right side for hours after the surgery. Paralysis hovered in the air as a possibility.

And then there was the clostridium difficile, a potentially fatal bacteria. She couldn't keep food down. She was infectious. She was quarantined. A hospital stay that should have been measured in days was extending to weeks, each low point sending her deeper than the last.

Forget about holding onto dreams of ever playing softball again. She just wanted to be able to walk from one side of the room to the other, which at the time felt like an impossible task.

Finally it was over and she was sent home, but she had paid a huge price. "I lost 20 pounds and all my strength. There was nothing left of me. I couldn't even walk up the stairs," she says.

But she was patient, and soon she would start to be rewarded for her efforts. First: getting back to feeling normal. Then she wanted more. The athlete who no longer had sports as an outlet for her competitive nature turned her focus on her recovery. Her physical therapy became her games.

Did she think she could do this? And could she do this again, but better than the week before? And was she ready to try something new and even more challenging?

After three months of hard work and progress, she was given intoxicating news. Things were going so well she might be released after six months, not the 12 they had warned her about. Then someone upped the ante. They mentioned she -- just maybe -- might be able to one day play softball again.

She found a calendar and started flipping through its pages. November, December, January, February. Six months would put it the week before her senior season of softball was set to begin with its opening practice. "That stepped up my competitive drive even more," she says.

She surprised almost everyone by pitching for Mountain View in its season opener that March, just not her dad. "She is a self-motivator. She is someone I'd call a grinder, someone who may not have four- or five-star athletic ability but has the will and desire to continuously improve," he says.

Later that spring Driscoll contacted Pinkerton and Meuchel. The player the coaches had written off -- but never forgotten about -- was back and pitching again. She would be starting school at Montana in the fall and wanted to know about tryouts.

"I had already accepted that I might never get to play softball again," she says. "I got to play my senior season and that summer. Whatever happened after that, great."

If the story ended there, of overcoming her brother's death, of not just making it through surgery but the life-threatening complications that came with it, of getting to play her senior year of softball and getting a college tryout, it could stand on its own as a righteous tale.

But the narrative continued, to Missoula, where in September 2015 Colleen Driscoll was given a tryout with the Grizzlies.

"She came in and was throwing 62. She was enticing with that velocity, and she had a pitch that others on our staff didn't utilize that much," says Meuchel. "She had a talent that could help us, so we knew we couldn't pass her up.

"And she looked good. She looked strong. She looked taller. Her shoulders were up and she looked confident, different than we had seen out recruiting." The surgery had worked.

Because of the timing and length of the tryout that fall and the paperwork that needed to be completed, Driscoll did not pitch for Montana during its autumn exhibition schedule.

Again, if the story ended here, of overcoming everything set in her path to become a Division I pitcher, it could stand on its own, but this is GoGriz.com Person of the Year territory. The story needed one more twist.

This will do: During her surgery, one of the vertebrae fusions did not hold. The titanium rods were in place, as were the seven hooks and 14 screws, but a section of her spine was going its own way again, bowing her upper back like it had been doing in the years prior to the procedure.

There was a battle taking place inside her, nature versus mechanics, Scheuermann's against titanium, something unstoppable facing something designed to be immovable. And no one knew it was occurring.

In early February of her freshman year, prior to one of the team's lifting sessions in the weight room, Driscoll bent over to put on her socks. Pop. The battle was over. Nature had won. The increasing curvature of her spine had put so much torque on the rods, both of them broke into two. Titanium rods.

You might think Driscoll would have been in pain, and you'd be right. But she just assumed it was her body continuing to come to terms with the new normal of her post-surgical life. What, you thought she was going to curl up in the fetal position and give in? Have you not been paying attention?

The player with all that inner drive went through weights "very painfully," she says. "By the time I got to practice, I could hardly move. I just thought it was stress and my body freaking out." Because who would have dared believe that what Scheuermann's was doing to her body was more powerful than titanium?

She took a week off of practice but still made her collegiate debut on Feb. 13, 2016, in the team's third game of the season. Facing Sacramento State in a nonconference game at Davis, California, she gave up three hits and two runs on 13 pitches in 2/3 of an inning.

Driscoll picked up her first win in relief in a home victory over Portland State and memorably pitched 9 1/3 innings of scoreless relief in Montana's 5-4 12-inning victory at North Dakota, gutting it out through 118 pitches. And no one knew what she was pitching through to do it, not even Driscoll.

She made 16 appearances that season, which wasn't a surprise. Montana needed her arm. But it was a surprise when she went for her one-year checkup in August 2016. They wanted to make sure everything was still in place, was looking solid and was working as intended.

Driscoll had made the team at Montana. She had pitched in a valuable role for the Grizzlies that spring as a freshman. No one suspected anything might be wrong or that she might have practiced, pitched and played the previous six months with broken rods in her back. It wasn't possible.

"The x-rays came up and the x-ray technician got really quiet," Driscoll recalls. "She asked me, 'Are you in pain?' When my doctor (who performed the surgery) came into the room, his head was down, and he could hardly look at me."

She would need surgery. Again. But when? She was just weeks away from starting her second year of college. Could it be delayed or did they need to take corrective measures immediately?

"The doctor said I didn't have any nerve damage and that I'd be fine putting it off. It would just be about managing pain," she says. She'd become an expert at that as a freshman, but it would only get worse as her sophomore year went along.

She lost a little bit from her curveball, but for the most part she was fine when she was pitching. It was sitting in the dugout and in class, riding on busses and flying on airplanes when the pain was almost unbearable.

So it's a little ironic that one of Driscoll's individual highlights last spring came when she made a start against No. 5 Oregon in Hawaii, in Montana's first game of the tournament after a long day of flying.

Driscoll threw the first four innings of what would be a 1-0 loss to the Ducks, who would go 54-8 and advance to the Women's College World Series in June.

Driscoll faced just 15 batters in four innings, three over the minimum, and needed to throw only 50 pitches. Oregon's only damage was a run-scoring single in the bottom of the fourth. Maddy Stensby pitched the final two innings, allowing just one hit in relief.

"That game really solidified everything for me," says Scott Driscoll. "She's literally competing against players on the U.S. national team, one after another.

"That was the seminal moment for me when it was, wow. Between her and Stens holding them to one run, to me that was, okay, you have reached it. From a dad's perspective, if you can prove yourself in the circle against that team, it says, yes, you can."

Not long after Montana defeated Weber State in the final game of the Big Sky tournament, when Driscoll came on in relief for the final 1 2/3 innings in the clincher, and not long after the Grizzlies made their NCAA tournament debut at Washington, Driscoll was back under the knife, in June.

She was cut open, again, from the base of her neck to her tailbone. The broken rods were removed, her spine was straightened and re-fused, new rods were inserted, and she was stitched back up. Again.

She was unable to play in the fall, and she still is on a 20-pound lifting restriction. She can pitch, but only throwing to a certain speed from shorter distances.

She finds out in early January if the new fusion held this time, if the figurative shackles can be taken off and she can get back to throwing full speed from 43 feet, when "I should be able to be an athlete again," she says.

Driscoll feels good. Really good. She is excited, full of anticipation of what is to come. She thought the first surgery was going to be the start of a new life, one free of burden, only to see it go awry. She is ready to give it another go.

"I feel good. For the first time since I broke the rods, I'm not constantly in pain," she says. "I didn't realize how much pain I was in (my first two years at Montana) until I came back this fall and started working out. I don't know how I did it."

Nor does Meuchel. As Montana's pitching coach and someone who had no experience handling someone in Driscoll's unique situation, she had to rely on feedback from her player. She gave Driscoll full control over when she would and wouldn't practice last season.

She didn't have to worry about Driscoll taking advantage of the situation. Driscoll had more than earned her coaches' trust.

"I would say maybe three times she took the day off the entire season," says Meuchel. "She is one of the toughest people I've ever been around. I don't think she truly knew the pain she was in, because that's all she'd known since she's been here."

Pitching is more than just the roundhouse rotation of the arm. It's about the legs and upper body working together, in sync, something that requires almost every part of the body to be involved in the mechanics of the motion, including the back.

"I don't know if Colleen ever fully had that strength in the past," Meuchel says. "It seems like everything is starting to work together just a little bit better. She looks really good. She seems to have a little more velocity."

Montana is loaded at pitcher this season, whether Driscoll is included on that list or not. There is Michaela Hood, first-team All-Big Sky last spring as a freshman and the MVP of the conference tournament. Maddy Stensby looked as good as she's ever looked in the fall.

Haley Young is back for her final season, and Tristin Achenbach is here for her first.

There is no timeline for Driscoll's return, and with the depth of the pitching staff, there doesn't need to be. Whether she pitches the opening weekend of the season in Phoenix or not until March or even April, Driscoll has already fulfilled what has turned out to be one of her most important roles for the Grizzlies.

"She has set a standard for our team with her work ethic and her strength and her mindset," says Meuchel. "Every time it gets really hard, the players can look over and see Colleen doing it. She has so much determination that she'll find a way to get it done, and that's a challenge to the rest of the team."

It's fitting that Driscoll isn't an overpowering strikeout pitcher, like Hood. She pitches to contact and is fine with that. She knows herself, better than most.

She had just 33 strikeouts last season, 145 fewer than Hood. But that's her game. She also only walked a dozen batters, the fewest by far of all the pitchers in the Big Sky who ranked in the top 12 in ERA.

Opposing hitters will make contact almost every at-bat. It just won't be solid very often.

"I've always been like that. I don't blow it past people," she says. "My goal is to spin it enough that you mis-hit it, and then I rely on my defense."

It's an apt metaphor for her life, don't you think? The hits are going to come. She has come to accept that. They arrive, she deals with them -- usually successfully -- and she moves forward. Next batter. Next obstacle. Come at me with everything you've got. You can bet I'm ready.

There was Quinn's death, the Scheuermann's diagnosis, the post-surgical complications, the setback that came from the rods in her back breaking. Then the second surgery and the recovery it required.

Support is all around her to deal with the hits, from wherever they might come. She has her family, her friends, her teammates in the field. Through everything, it's probably the most important lesson she's learned. She may stand alone in the circle, but she's got her battery mate and seven players behind her.

"It's not necessarily a safety net, more, Hey, it's going to be okay," says Scott. "They're going to get a few hits off you but we have your back. I think that makes you a stronger player and a stronger person as well."

And it makes Colleen Driscoll, she of the orange ribbon in her hair and now wholly intact back, the 2017 GoGriz.com Person of the Year.

What did you see when she stood inside the circle, which she did 25 times last spring, when Montana was winning a Big Sky Conference championship? Just another loaded arm on a staff of them, which the Grizzlies rode to the NCAAs?

Did you recognize the ribbon on the days she pitched? Or know what it represents or the weight it carries? How it connects her to a tragedy that took place in 2009? And no matter how badly she'd like to lose the hurt, how she never wants to forget that June day or lose the connection to her brother?

Did you know about the hardware, 23 pieces in all, that she pitched with, a titanium scaffolding that encased her spine from the base of her back to the base of her neck? Or how the most important pieces, the rods that paralleled her backbone, had both snapped in two more than a year earlier?

You saw a sophomore pitcher who became an NCAA tournament team's No. 2 starter. Who finished the season with an ERA of 2.98, the sixth-best average in the Big Sky.

What you probably didn't see was the orange ribbon, a game-day symbol of perseverance and remembrance. Or know about the broken rods in an already compromised back, or how a system of hooks and screws, installed to free her from Scheuermann's kyphosis, had become a millstone.

Or realize the strength it took for Colleen Driscoll simply to make it through each day, much less emerge as a key player on a championship team.

"Hands down the most mentally tough, determined person I've ever coached, and it's not even close," says former Montana coach Jamie Pinkerton, now at Iowa State, who's been coaching at the Division I level for more than two decades.

There is not a written set of criteria that is used when determining the GoGriz.com Person of the Year, which is being handed out for the third time this Christmas.

The award's first two recipients -- Emily Mendoza and Jessica Bailey -- were both recognized for the work they did for others, both going on service trips to Africa as part of their undergraduate experience and education.

Colleen Driscoll is this year's honoree and is not at all like Mendoza and Bailey, at least for the reason she is this year's recipient. While Mendoza and Bailey were chosen for the things they did for others, Driscoll is the 2017 GoGriz.com Person of the Year for what she's done just to get herself to this point.

"I've never heard of anything like she's gone through," says Pinkerton. "I would understand if the kid threw her hands up and said, I've had enough. I can't handle this anymore. But she never has. That's why she's one of the most special players I've ever had the privilege of coaching."

The question, then, becomes this: Have the circumstances of Colleen Driscoll's life made her the person she is -- strong, resilient, tough, unbreakable, a new descriptor for each new hurdle cleared -- or was she that person from the start, uniquely prepared to handle every new obstacle placed before her?

Did bending over to put on a pair of socks her freshman year at Montana and feeling a pop in her back -- not knowing two titanium rods, placed a year and a half earlier and thought to be indestructible, there for life, had just broken -- make her stronger?

Or was she already a driven athlete, who assumed the pain that washed over her that day was just her body continuing to adapt post-surgery and followed through with that day's weight-room workout without giving it a second thought?

What about the complications from the surgery she underwent the August before her senior year at Mountain View High in Vancouver, Washington, when things spiraled out of control, when there were fears of paralysis and later the onset of an infection that led to her being quarantined?

Or the news she received as an eighth grader, when a doctor told the Driscolls that it wasn't the poor posture of a lazy teenager that was afflicting their daughter, it was Scheuermann's and that she would one day need back surgery?

Or two years before that, as a sixth grader, when her school was put into emergency lockdown, when she was escorted by security out of her classroom and taken to her dad, who she saw crying for the first time in her life, who had to break the news to her about her brother and best friend?

Did all those experiences make the girl, or was Driscoll just born with it, provided with all she'd need from the start to handle everything that was going to be thrown her way?

"She had that as a 4-year-old," says Scott Driscoll, Colleen's dad. "I wish I had a tenth of what she has from that standpoint."

The Driscolls were a foursome before Colleen arrived, with Scott working in computer software in Portland, Kelly in finance at Nike in Beaverton.

With Kaylyn and Quinn already in the mix, kid No. 3 tipped the balance. It could no longer be one-to-one supervision when it came to youth sports. And since Colleen was always tagging along anyway, watching everything, processing, taking it all in, she might as well be put in tee-ball to see how she did.

"Even at that age she was an amazing observer of the games when her older siblings were playing," says Scott. "When she finally got on the field, it was like she had been playing for years, even though she was just a little kid."

See Quinn, a year and a half older than Colleen, but the two often together on the same age-group teams, looking so much alike and chumming like besties that people assumed they were twins.

And see the Johnson family, whose three children matched up in age perfectly with the Driscolls: the older sisters, then Ryan and Quinn, then Kendall and Colleen, all of them being pulled toward sports, none more so than Quinn, who by the eighth grade was emerging as a three-sport standout.

So no one would have thought anything of it that June day in 2009, not long before school would be out for the summer, the final step before Quinn could enter high school and play football, basketball and baseball at a higher, more competitive level, when he was racing around the track in PE class.

All of it -- his potential, his future, his talent -- was on display as he made his way around the final lap of the one-mile race, still enough remaining in the tank that he could be heard urging on his classmates.

But the very thing that was the engine of it all, his heart, gave in, no longer able to power Quinn's dreams. He fell to the track, a victim of sudden cardiac arrest. What no one could have known or would have guessed was that he was a victim of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The school was placed in a medical lockdown. Teachers and emergency responders tried to revive Quinn. Security was sent to find Colleen. "They just told me my brother fell," she says.

She was brought to the front of the school. That's odd, she thought, why is my dad here? "I'd never seen him cry before, so I knew something was wrong." Quinn did not survive. Colleen had lost her best friend. A family was faced with a tragedy.

Another question: Did Colleen gain strength from the rest of her family in the days that followed, or was it the other way around? Or was it a collective effort to support one another as they moved on, all wanting to do something that would make sure Quinn would never be forgotten?

"Colleen was presented with two paths," says Scott. "You can either give up and let people feel sorry for you or you can go out and do things with even more purpose, like I'm going to dedicate this to my brother. That's what she was thinking."

The family as well, who quickly set up the Quinn Driscoll Foundation, because they didn't want another family to have to go through what they'd just experienced. Instead of closing in as a family, they opened up and shared Quinn's story, balancing the suffering with the good they wanted to come out of it.

"You can have a tragedy like that and say how horrible it was that we lost our 13-year-old son, or you can do something about it and try to turn tragedy into something positive," Scott says.

Today the foundation has two goals: the education and screening of youth for issues associated with sudden cardiac arrest and the distribution of automated external defibrillators.

Would a screening have saved Quinn's life? No one knows for certain, but it very likely could have. The foundation isn't keeping track of potential lives saved through its work and outreach. There was the first, way back when, one family spared the heartache, and that was enough for the Driscolls.

"If we help one family, if we help one kid, we've done our job. That was kind of our motto from the start and still is. We kind of stopped counting at one save," says Scott.

The foundation is based in Vancouver, but its reach has extended to Missoula, in more ways than Quinn's younger sister pitching for the Grizzlies. Step inside the indoor hitting facility behind Grizzly Softball Field and you'll find an AED, courtesy of the Quinn Driscoll Foundation.

"It's not only there for the players who use that facility but for the hundreds and even thousands of people who are out there on an annual basis. To have that life-saving device is what it's all about," says Scott.

Because of the AED, Quinn Driscoll has a permanent presence at Grizzly Softball Field. He might also come to mind, from now on, when Colleen Driscoll steps out of the dugout and walks toward the circle sporting her own game-day memorial. His presence will be all around.

"Orange was Quinn's favorite color. He dreamed of playing college baseball and never got the opportunity. I get it for both of us," says Driscoll, who has had postural issues dating back to her early years.

If scoliosis is an S bend of the spine when looking at someone from behind, Scheuermann's presents itself as a C when looking from the side. Vertebrae grow unevenly, which leads to abnormally excessive curvature.

When nobody knew that Driscoll had Scheuermann's, everyone just assumed she needed to be told how to carry herself. "My parents would yell at me to stand up straight. They figured I had bad posture, but I couldn't straighten up," Driscoll says.

It wasn't until the eighth grade that she was finally diagnosed. It was more of an aha moment than alarming news. It explained a lot and came with a prediction that she would probably need surgery at some point, years and years down the road.

At least it wasn't going to hold her back now, when she had so much she wanted to accomplish. And didn't years and years down the road sounds like another lifetime to an eighth grader, something she might need to address as an adult? At least it wasn't going to affect her childhood, thank goodness.

"Surgery was never in question. My doctor said that was a last resort," says Driscoll.

The ACL tear she suffered in eighth grade playing basketball put an end to the promise she showed in that sport. She played volleyball as a sophomore and junior, once her knee had healed, but it became mostly about softball, first in high school and club, then with a goal of playing it in college.

She was good enough that she caught the eye of Montana's coaches, who were in the process of starting a program.

"What we really liked was that she was a tall, strong individual with good fundamentals," said then pitching coach and now head coach Melanie Meuchel. There were concerns but only because the coaches didn't know the entire story.

"She always had her shoulders down and her head down. She competed and was into what she was doing, but it felt like there might be a confidence issue. You just wanted her to be a little more confident and put her shoulders up. Little did we know."

And little did Driscoll know about the next trial that was coming her way. In the spring of her junior year she saw her doctor for her annual exam. She expected it to be routine, to be told the same thing, that there was nothing to be concerned about at this point. To keep on doing what she was doing.

What she heard turned her world upside down. She had faced a life-changing event as a sister years before. Now she was forced to do it again as a softball player, facing her mortality as an athlete.

"The doctor came in and said, I think you need surgery," Driscoll recalls. "I was like, What? It's hard at 17 to accept that your dreams of playing college softball are literally over in a 20-minute doctor's visit."

The effects of Scheuermann's were advancing faster than anyone had anticipated. The degree of curvature of her spine had gone beyond what was considered safe. If it wasn't corrected, it was going to start affecting her health.

Sections of her spine where vertebrae had formed like wedges would need to be broken, straightened and fused back together. Bracketing it all together would be the 23 pieces of titanium, including the two rods that would extend from her T3 to her L2, in other words from top to bottom.

It didn't need to be an emergency surgery but it had to happen sooner than anyone wanted.

The decision she had to make was, when would she undergo the procedure? Finish out her senior season in high school, then go under the knife? But she wanted to go to college too and not put that on hold. And what about playing softball in college? And going to physical therapy school after that?

Since the recovery would require some down time, followed by extensive physical therapy, there was no good answer. Well, there was, but Driscoll wasn't ready to think about it. Was she prepared to sacrifice her senior season playing for the Thunder? Was she ready to admit her softball career might be over?

"He recommended doing it while I was young, so I could recover at home. There is no good time in college to do that, so I had to look at life in a bigger picture," says Driscoll, who also knew she had to contact the coaches of the schools that were interested in her and tell them the news.

That meant reaching out to Montana, which had become her No. 1 school, thanks to family friend Ryan Johnson, who ended up playing football for the Grizzlies. The defensive end was third-team All-Big Sky Conference in 2016 as a fifth-year senior.

The Johnsons were the ones who let the Driscolls know Montana was starting a softball program. It only took one visit to Missoula to watch one of Johnson's football games for Driscoll to discover the school of her dreams.

"I fell in love with it, and that was my biggest thing. I wanted to find a school I loved no matter what, whether I was playing softball or not," says Driscoll.

She decided to schedule the surgery for August, before the start of her senior year. Because there were no guarantees she would ever play softball again, it gave the final games of her junior season at Mountain View and her club team's tournaments that summer the feel of a possible farewell tour.

Was she making the final start of her career? Of her life? Had she just thrown her final curveball? Had she just had an in-game meeting with her catcher for the final time? Had she just taken her final bus trip with teammates who would be friends for life? What was out there that could ever replace this?

Wanting to extend the dream as long as possible, she waited until the day before her surgery to finally break the news to Montana's coaches. Her message: Thanks but you should probably move on. It was a disappointment felt on both sides.

"She let us know she had to undergo a procedure and didn't know if she'd ever play softball again," says Meuchel. "She said she appreciated us watching and following her but feel free to move on with the recruiting process. It was a bummer. We thought this kid had a chance."

The procedure wasn't necessarily going to be the end of her pitching career, but she knew she needed to prepare herself for the possibility. Just like she knew she needed to be ready for the long haul. Her doctor warned her the recovery from the surgery could take up to 12 months.

That was if everything went according to plan, which it didn't. During the surgery the dura mater enveloping her spinal cord was cut. Fluid leaked, leading to painful spinal headaches. And she had no feeling on her right side for hours after the surgery. Paralysis hovered in the air as a possibility.

And then there was the clostridium difficile, a potentially fatal bacteria. She couldn't keep food down. She was infectious. She was quarantined. A hospital stay that should have been measured in days was extending to weeks, each low point sending her deeper than the last.

Forget about holding onto dreams of ever playing softball again. She just wanted to be able to walk from one side of the room to the other, which at the time felt like an impossible task.

Finally it was over and she was sent home, but she had paid a huge price. "I lost 20 pounds and all my strength. There was nothing left of me. I couldn't even walk up the stairs," she says.

But she was patient, and soon she would start to be rewarded for her efforts. First: getting back to feeling normal. Then she wanted more. The athlete who no longer had sports as an outlet for her competitive nature turned her focus on her recovery. Her physical therapy became her games.

Did she think she could do this? And could she do this again, but better than the week before? And was she ready to try something new and even more challenging?

After three months of hard work and progress, she was given intoxicating news. Things were going so well she might be released after six months, not the 12 they had warned her about. Then someone upped the ante. They mentioned she -- just maybe -- might be able to one day play softball again.

She found a calendar and started flipping through its pages. November, December, January, February. Six months would put it the week before her senior season of softball was set to begin with its opening practice. "That stepped up my competitive drive even more," she says.

She surprised almost everyone by pitching for Mountain View in its season opener that March, just not her dad. "She is a self-motivator. She is someone I'd call a grinder, someone who may not have four- or five-star athletic ability but has the will and desire to continuously improve," he says.

Later that spring Driscoll contacted Pinkerton and Meuchel. The player the coaches had written off -- but never forgotten about -- was back and pitching again. She would be starting school at Montana in the fall and wanted to know about tryouts.

"I had already accepted that I might never get to play softball again," she says. "I got to play my senior season and that summer. Whatever happened after that, great."

If the story ended there, of overcoming her brother's death, of not just making it through surgery but the life-threatening complications that came with it, of getting to play her senior year of softball and getting a college tryout, it could stand on its own as a righteous tale.

But the narrative continued, to Missoula, where in September 2015 Colleen Driscoll was given a tryout with the Grizzlies.

"She came in and was throwing 62. She was enticing with that velocity, and she had a pitch that others on our staff didn't utilize that much," says Meuchel. "She had a talent that could help us, so we knew we couldn't pass her up.

"And she looked good. She looked strong. She looked taller. Her shoulders were up and she looked confident, different than we had seen out recruiting." The surgery had worked.

Because of the timing and length of the tryout that fall and the paperwork that needed to be completed, Driscoll did not pitch for Montana during its autumn exhibition schedule.

Again, if the story ended here, of overcoming everything set in her path to become a Division I pitcher, it could stand on its own, but this is GoGriz.com Person of the Year territory. The story needed one more twist.

This will do: During her surgery, one of the vertebrae fusions did not hold. The titanium rods were in place, as were the seven hooks and 14 screws, but a section of her spine was going its own way again, bowing her upper back like it had been doing in the years prior to the procedure.

There was a battle taking place inside her, nature versus mechanics, Scheuermann's against titanium, something unstoppable facing something designed to be immovable. And no one knew it was occurring.

In early February of her freshman year, prior to one of the team's lifting sessions in the weight room, Driscoll bent over to put on her socks. Pop. The battle was over. Nature had won. The increasing curvature of her spine had put so much torque on the rods, both of them broke into two. Titanium rods.

You might think Driscoll would have been in pain, and you'd be right. But she just assumed it was her body continuing to come to terms with the new normal of her post-surgical life. What, you thought she was going to curl up in the fetal position and give in? Have you not been paying attention?

The player with all that inner drive went through weights "very painfully," she says. "By the time I got to practice, I could hardly move. I just thought it was stress and my body freaking out." Because who would have dared believe that what Scheuermann's was doing to her body was more powerful than titanium?

She took a week off of practice but still made her collegiate debut on Feb. 13, 2016, in the team's third game of the season. Facing Sacramento State in a nonconference game at Davis, California, she gave up three hits and two runs on 13 pitches in 2/3 of an inning.

Driscoll picked up her first win in relief in a home victory over Portland State and memorably pitched 9 1/3 innings of scoreless relief in Montana's 5-4 12-inning victory at North Dakota, gutting it out through 118 pitches. And no one knew what she was pitching through to do it, not even Driscoll.

She made 16 appearances that season, which wasn't a surprise. Montana needed her arm. But it was a surprise when she went for her one-year checkup in August 2016. They wanted to make sure everything was still in place, was looking solid and was working as intended.

Driscoll had made the team at Montana. She had pitched in a valuable role for the Grizzlies that spring as a freshman. No one suspected anything might be wrong or that she might have practiced, pitched and played the previous six months with broken rods in her back. It wasn't possible.

"The x-rays came up and the x-ray technician got really quiet," Driscoll recalls. "She asked me, 'Are you in pain?' When my doctor (who performed the surgery) came into the room, his head was down, and he could hardly look at me."

She would need surgery. Again. But when? She was just weeks away from starting her second year of college. Could it be delayed or did they need to take corrective measures immediately?

"The doctor said I didn't have any nerve damage and that I'd be fine putting it off. It would just be about managing pain," she says. She'd become an expert at that as a freshman, but it would only get worse as her sophomore year went along.

She lost a little bit from her curveball, but for the most part she was fine when she was pitching. It was sitting in the dugout and in class, riding on busses and flying on airplanes when the pain was almost unbearable.

So it's a little ironic that one of Driscoll's individual highlights last spring came when she made a start against No. 5 Oregon in Hawaii, in Montana's first game of the tournament after a long day of flying.

Driscoll threw the first four innings of what would be a 1-0 loss to the Ducks, who would go 54-8 and advance to the Women's College World Series in June.

Driscoll faced just 15 batters in four innings, three over the minimum, and needed to throw only 50 pitches. Oregon's only damage was a run-scoring single in the bottom of the fourth. Maddy Stensby pitched the final two innings, allowing just one hit in relief.

"That game really solidified everything for me," says Scott Driscoll. "She's literally competing against players on the U.S. national team, one after another.

"That was the seminal moment for me when it was, wow. Between her and Stens holding them to one run, to me that was, okay, you have reached it. From a dad's perspective, if you can prove yourself in the circle against that team, it says, yes, you can."

Not long after Montana defeated Weber State in the final game of the Big Sky tournament, when Driscoll came on in relief for the final 1 2/3 innings in the clincher, and not long after the Grizzlies made their NCAA tournament debut at Washington, Driscoll was back under the knife, in June.

She was cut open, again, from the base of her neck to her tailbone. The broken rods were removed, her spine was straightened and re-fused, new rods were inserted, and she was stitched back up. Again.

She was unable to play in the fall, and she still is on a 20-pound lifting restriction. She can pitch, but only throwing to a certain speed from shorter distances.

She finds out in early January if the new fusion held this time, if the figurative shackles can be taken off and she can get back to throwing full speed from 43 feet, when "I should be able to be an athlete again," she says.

Driscoll feels good. Really good. She is excited, full of anticipation of what is to come. She thought the first surgery was going to be the start of a new life, one free of burden, only to see it go awry. She is ready to give it another go.

"I feel good. For the first time since I broke the rods, I'm not constantly in pain," she says. "I didn't realize how much pain I was in (my first two years at Montana) until I came back this fall and started working out. I don't know how I did it."

Nor does Meuchel. As Montana's pitching coach and someone who had no experience handling someone in Driscoll's unique situation, she had to rely on feedback from her player. She gave Driscoll full control over when she would and wouldn't practice last season.

She didn't have to worry about Driscoll taking advantage of the situation. Driscoll had more than earned her coaches' trust.

"I would say maybe three times she took the day off the entire season," says Meuchel. "She is one of the toughest people I've ever been around. I don't think she truly knew the pain she was in, because that's all she'd known since she's been here."

Pitching is more than just the roundhouse rotation of the arm. It's about the legs and upper body working together, in sync, something that requires almost every part of the body to be involved in the mechanics of the motion, including the back.

"I don't know if Colleen ever fully had that strength in the past," Meuchel says. "It seems like everything is starting to work together just a little bit better. She looks really good. She seems to have a little more velocity."

Montana is loaded at pitcher this season, whether Driscoll is included on that list or not. There is Michaela Hood, first-team All-Big Sky last spring as a freshman and the MVP of the conference tournament. Maddy Stensby looked as good as she's ever looked in the fall.

Haley Young is back for her final season, and Tristin Achenbach is here for her first.

There is no timeline for Driscoll's return, and with the depth of the pitching staff, there doesn't need to be. Whether she pitches the opening weekend of the season in Phoenix or not until March or even April, Driscoll has already fulfilled what has turned out to be one of her most important roles for the Grizzlies.

"She has set a standard for our team with her work ethic and her strength and her mindset," says Meuchel. "Every time it gets really hard, the players can look over and see Colleen doing it. She has so much determination that she'll find a way to get it done, and that's a challenge to the rest of the team."

It's fitting that Driscoll isn't an overpowering strikeout pitcher, like Hood. She pitches to contact and is fine with that. She knows herself, better than most.

She had just 33 strikeouts last season, 145 fewer than Hood. But that's her game. She also only walked a dozen batters, the fewest by far of all the pitchers in the Big Sky who ranked in the top 12 in ERA.

Opposing hitters will make contact almost every at-bat. It just won't be solid very often.

"I've always been like that. I don't blow it past people," she says. "My goal is to spin it enough that you mis-hit it, and then I rely on my defense."

It's an apt metaphor for her life, don't you think? The hits are going to come. She has come to accept that. They arrive, she deals with them -- usually successfully -- and she moves forward. Next batter. Next obstacle. Come at me with everything you've got. You can bet I'm ready.

There was Quinn's death, the Scheuermann's diagnosis, the post-surgical complications, the setback that came from the rods in her back breaking. Then the second surgery and the recovery it required.

Support is all around her to deal with the hits, from wherever they might come. She has her family, her friends, her teammates in the field. Through everything, it's probably the most important lesson she's learned. She may stand alone in the circle, but she's got her battery mate and seven players behind her.

"It's not necessarily a safety net, more, Hey, it's going to be okay," says Scott. "They're going to get a few hits off you but we have your back. I think that makes you a stronger player and a stronger person as well."

And it makes Colleen Driscoll, she of the orange ribbon in her hair and now wholly intact back, the 2017 GoGriz.com Person of the Year.

Players Mentioned

Griz Football Coach Bobby Kennedy Introductory Press Conference

Friday, February 06

Bobby Kennedy Introductory Press Conference

Thursday, February 05

Griz TV Live Stream

Thursday, February 05

Lady Griz vs. Portland State Highlights - 1/29/26

Wednesday, February 04