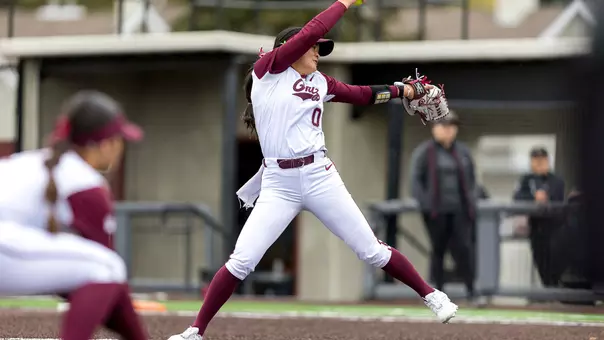

Photo by: Tanner Ecker/UM Photo

Origin Stories :: Nyeala Herndon

1/17/2024 6:26:00 PM | Softball

It's one of the best parts of Montana softball coach Melanie Meuchel's job, to be able to play dream-maker, to be able to sit down with an athlete who has imagined this happening, longed for it, with parents who have sacrificed to get their daughter here, for Meuchel to be able to offer another player the chance to play Division I softball, to share in that intensely emotional family moment.

Granted, for some it's more transactional, Montana the best or most appealing option of the many on the table, the end result – college softball – always the understood or expected destination, with only the particulars – the school, the scholarship offer – to figure out. Those are fun but don't produce quite the same feels.

And then there are some, like the day she sat down with Aspen and Nyeala Herndon, that just hit differently, layers of feelings to unpack and try to handle, Aspen never getting the chance to play college softball because of the era and growing up in small-town Montana, Nyeala falling for the Grizzlies that day at home in Helena when Montana played in the NCAA tournament in 2017 on ESPN, now realizing the long-held hope of playing for her home-state team.

It was the best. "We had a real special visit with her," says Meuchel. "We talked about what we had here for Ny, knowing how special it would be for her to be in Missoula and close to home, close to her family and be able to compete for a state she really loves. As we talked through things, you could see how special this opportunity would be, one she didn't know would be available for her. Pretty special moment."

Then the Herndons shared with Meuchel the deeper reason for all the tears, beyond the more typical ones, of hard work paying off, of a childhood dream of playing college softball coming true. They told Meuchel a life story, of facing death, of overcoming the odds that predicted this would never happen, that Nyeala would never be here. A story that answers the question: Do you really think pitching in a tight game with runners on second and third is going to faze Nyeala Herndon?

It started with a low-grade fever, the inability to keep food down when she was seven months old. Must be teething, Aspen was told when she called in with her concerns. But bring her in if you think it's serious. It was. A stethoscope found no sounds coming from her left lung, nothing functioning, nothing coming in, nothing going out. And just like that, Nyeala Herndon was in a fight for her life, and she was on the ropes, on the way to losing by knockout, blindsided. She would have had no idea what was happening, why everyone was suddenly in crises mode.

Dr. Dennis Ruggerie, who spoke about Herndon's case for this article with consent from the family, happened to be in Helena that day, at an outreach clinic from his normal post in Great Falls, he the state's first-ever full-time pediatric cardiologist living and working in Montana when he was hired in 1989.

He was contacted, told the particulars. How serious was it? He dropped everything he was doing and scheduled to do, and immediately ordered a helicopter transport to fly from Great Falls to Helena to pick Herndon and her mom up and take them back to Great Falls, knowing the saving of even a few minutes might make a life-and-death difference. "It was very clear she was critically ill and we needed to get her to Great Falls to our pediatric ICU," Ruggerie says.

The antagonist was a non-threatening-sounding cold virus, though Herndon had just overcome a case of RSV (respiratory syncytial virus). This new adversary found a weak link, her heart, and went into attack mode. All out, full on. Herndon was intubated and put on a breathing machine, IVs were quickly inserted, medicines pumped into her bloodstream to give her body a fighting chance at making it one more hour, one more hour, one more hour, life going, in half a day, from routine to perilous, skipping all the steps in between, from healthy to just holding on. "Her heart was working at a level that was incompatible with survival without our critical-care technology and drug-therapy support," says Ruggerie. "Her heart was failing." She was suffering from myocarditis.

A normal heart operates at 55-65 percent efficiency, its pump filling with blood, then contracting and ejecting blood into the arteries, 55 to 65 percent of the available blood getting discharged. That's normal. Herndon's number was dropping by the hour, like a countdown clock ending in the worst-case scenario, the virus winning its fight against the heart, the battle for Herndon's life. Forties, thirties, twenties, teens, single digits. "She was probably less than five to seven percent. They are all bad numbers when it's under 12 percent. Those are incompatible with survival," Ruggerie says.

Aspen had had six months of bliss at home with her firstborn, fretting over the usual things, the temperature of the fluid in the feeding bottle, the contents of her daughter's crib, the right toys to stimulate proper development skills. Now, when every motherly instinct screamed at her to do something, to fight for her daughter, she was left as a spectator as nurses and doctors did things to and for Nyeala that her mom will never be able to unsee.

The tiny patient was sedated to mask the pain of the horrors being inflicted upon her fragile body. Nothing exists for a parent in that moment. Sleep won't come. Fatigue and emotions that have run dry result in a downward spiral until a parent is in a haze, almost watching the proceedings like it's an out-of-body experience, their real person no longer capable of tapping into an empty reservoir of strength and energy.

"Aspen saw us doing things to her baby that she couldn't comprehend," says Ruggerie. "It was an absolute nightmare, but she was very strong and listened very well. She trusted us. We needed her to trust us." Herndon was stabilized but still teetering on that fine edge between life and death, the longer she was there, the longer she was needing all-out support, the less likely the end result was going to be a good one.

Ruggerie got into pediatric cardiology, a profession not for the weak of (ahem) heart, not because of some divine calling but because he didn't understand it, "and that bothered me," he says. "I understood adult cardiology well, general medicine issues well and had very good training in pediatrics. I just had a hard time understanding congenital heart disease, so I thought I would take the challenge."

He graduated from the Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine in 1981, did an internship at Grandview Hospital in Dayton, then a residency at Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, then a fellowship at the same hospital.

I have a friend who is an emergency room doctor in Duluth, Minn. He says he's come to be able to handle the arrival of death in his presence for anyone over the age of 30 or 40 by accepting that they were able to experience most of the great "firsts" in life if they chose to do so. The first time falling in love. First job. First birth of a child. It's how he can sleep at night after a particularly rough shift. But how does a guy handle a career in pediatric cardiology, when every patient has never had a first in life, when every patient he sees is at their most vulnerable in life?

"It takes different people to do different kinds of work," Ruggerie says. "I always wanted to be a person who others came to for help, whatever comes through the front door. I wanted to be that guy and part of the team of people who were ready to meet the challenge, stabilize kids, treat kids, help them get better, whether the child was born to survive or had a fatal injury."

A child comes into his life and the full spectrum of end results is at play, an early death and grieving parents to the first step toward recovery and a life that may span decades and decades and decades, and who knows what that person might accomplish? It's a big burden to carry, being the one who willingly takes on that load.

"You learn to compartmentalize the sad outcomes and stay in the action by following your assessment skills, your algorithms, your pathways, making sure you do the same thing over and over and over again, no matter how sick the child is," he says. "You keep thinking your way through it and try to keep your emotions in a box. If you're leading a team, you need to present a strong position to keep the other team members focused and strong so we don't miss an opportunity to actually save a child."

Who better to have watching over your child when life – and everything you thought it was going to be, for you, for your daughter – is unraveling before your eyes? Nyeala Herndon's heart was failing. The virus was still on the attack, doing more damage, some of it potentially irreversible, by the hour. Her heart was dying. With everything going against her, she remained in the best of hands.

The entire thing becomes a chess match for Ruggerie, he says, of thinking two, three, four moves ahead. He met with Aspen every two hours, to fill her in on the status of her daughter, what her options were, one of them, at the very worst of moments, to prepare to be with her daughter as she passed away, the virus doing so much damage to Nyeala's seven-month-old heart that even Ruggerie and his team couldn't overcome it. Another, a long shot, a life flight to Salt Lake City and Primary Children's Hospital to get on the list for a heart transplant, something that had to happen now, right now, because another day of worsening and weakening and Herndon would never have been able to survive the stress of the flight. Big moments, little time to decide.

It became a numbers game. "The outcome expectations were that Nyeala had one-third chance of dying, one-third chance of surviving with her heart ultimately returning to normal, though that may take years, and one-third chance of surviving with a damaged heart and long-term heart failure," Ruggerie says. It was as dark as it could get for the family, knowing the idea of a transplant offered a small light of hope but knowing the wait, if it came to it, would almost certainly come to an end before a heart, just the right size, healthy enough to survive, became available.

She's here, about to play her freshman season of Division I softball, so you know how it ended up. Within days of arriving in Salt Lake, her heart, with plenty of medical help, started to win the fight, started to get the upper-hand on the virus, though the effects of the battle would be long-lasting, her heart ravaged, a pugilist surviving but showing the scars, asked to do what it wasn't designed to.

She got off ICU support, then after three months was taken off the transplant list, then, after four months at Primary's Children's Hospital, was allowed to return to Great Falls, where Aspen and Nyeala lived in the local Ronald McDonald House for easier access to her multiple appointments each week. She was on the road to recovery but it was a long one and they were only just starting their journey.

At age 5, her number of medications dropped from five to two, clinic visits tapered off to monthly, to every six months, to yearly. Eventually she was weaned off all medications and last summer she underwent a cardiac MRI that revealed, for the first time since she was six months old, an absolutely normal heart, a plain old boring and most beautiful heart, just doing its thing. The scarring was gone and there had been a regrowth of the damaged heart cells. It only took 17 years to get there.

"We had a lot of good luck, she got a lot of good care and we had a lot of good prayers," says Ruggerie, whose clinic is located at 2510 Bobcat Way but gave his best to a future Grizzly anyway. "She has become a quiet, pleasant, smart young lady with a mother who is very dedicated to her. I think she had it in her to begin with because her mother does. It's a great story any way you want to look at it."

So, yeah, some visits between Meuchel and a prospective player and a parent, when an offer is made to play Division I softball for the Grizzlies, just mean a little bit more. "It's a story we don't like to rethink but when we do and think about everything we've been through as a family, it's very humbling," says Aspen. "To see her success despite everything she's had to fight has been amazing."

Call it life's payback, a special gift presented to those who are born prematurely or who go through myocarditis or in some other way have to fight for life before they're even aware they're doing so. They take away a little bit of something special from the experience, something they can apply to the rest of their lives. NICU nurses swear by it, a fighting spirit acquired for life.

"I don't know if it's because of what she went through, but when she has to rise to the occasion, she rises," says Aspen. "She's just always had that in her. I've seen that academically in her, I've seen it at home with her. She's always been that kid. Then when it's done, she goes back to her quiet, reserved self."

Of course, there were some lingering effects of the ordeal, both physical (for Nyeala) and mental (for Aspen), mom filling with worry every time her daughter took off running down the street. After all, how could a heart that had gone through what Nyeala's had be up for supporting a fully active lifestyle?

Thank goodness she was at first interested in art. No stress there! Same for dance and gymnastics. Same for tee-ball, all low on the exertion level. We're all good, right mom? Then her friends started playing softball, and Nyeala wanted to join. Uh-oh. Mom kept worrying about limitations and what her daughter's sporting ceiling would ultimately be based on her heart and its restrictions. Nyeala wanted to break through them, her spirit begging her heart to keep up – let's go! – mom both scared and amazed at the same time at what was happening, the envelop being pushed when no one could say for sure what was too far or what the end point might be.

Aspen had grown up watching her own mom play slow-pitch softball in Townsend, finally joined in when she was 14. "Loved it, loved it," she says. She kept playing it in Helena, bringing her daughter, then daughters, along.

Coaching? A 10-year-old interested in pitching? She tapped every resource she could in Helena, watched YouTube videos of Cat Osterman and Jenny Finch, took Nyeala to private lessons, absorbed all the teachings herself, learning enough that today she has a side gig, along with being a college and career counselor at Capital High, as the pitching coach at Carroll College.

"Trying to make sure we were doing it safely and getting her to where she could be successful at it, whatever level that was at the time," says Aspen, who began coaching her daughters' teams and who perhaps unintentionally developed a Division I pitcher by intentionally not handing the starting job to her daughter just because she was the coach's daughter and wanted to pitch. You want it? Go out and earn it. Become so good that I have no other choice but to use you as my ace. "I'm a lot harder on them than other kids," she says. "You've got to go put in the work if you want to be our starting pitcher. I'm not just going to give you the position." Can you feel it? Mom growing stronger as her daughter's heart did the same thing, mom coming out of her uneasiness, mom gently pushing now? You can do it.

She became a pretty big deal, Nyeala did, at least in Montana. That was fine, but people saw something more in her, greater than simply pitching high school ball in the state. It was time spent with Morgan Ray, who starred at Frenchtown High before pitching at Ohio State, that convinced the family that being a big fish in a small pond didn't need to be Herndon's end game or future. She had the stuff to pitch collegiately.

Herndon was playing at a tournament in Oklahoma City when she got an email from someone with the Washington Ladyhawks, who have one of the best travel-ball organizations in the Northwest. And would Herndon like to join them? It would be her ticket to the larger world of age-group softball.

It's just what she needed. Pitches on the outer half of the plate, which worked for her in Montana, were ripped for base hits the other way. Pitches when she missed by an inch or two weren't fouled off, they were smoked for extra bases. Even when she was perfect with her spin and placement, she could still get hit hard. She had to get better. She had just seen if firsthand.

"It was eye-opening that there was another level that players in Montana don't really know about," Herndon says. "It was eye-opening to see the difference, their knowledge of the game, their pitch selection and their mechanics. It was more college-level than I was used to."

Nature, those experiences she went through, perhaps some nurture, has led her to have an ideal composition for a pitcher, someone who has the equanimity to realize that it's just softball blended together with that rise-to-the-occasion toughness. A blend of competitiveness with a life-is-bigger-than-softball mindset. And it works.

At a 12U tournament, facing, if they remember correctly, Kynzie Mohl on the other team, Herndon pitched a silver-platter special, and Mohl did what she's always been doing to those pitches. She sent it screaming over the fence. "She lays this fat pitch across the plate and she just sends it yard," recalls Aspen. It was the kind of home run that would have sent most pitchers that age asking to be repositioned to the outfield. "Nay turned to the dugout, looked at us and shrugged her shoulders," says her mom. "She got the ball back and struck out the next one. She has always not let it get to her on the mound."

She doesn't have it all figured out, no matter how rosy and uplifting her story may read. She wants you to know that. And she wants you and athletes who come behind her to know that it's okay to not only not have it figured out but to admit it. And to seek help.

When she was a sophomore, she made the varsity volleyball team at Capital High, playing alongside Paige and Dani Bartsch, who are playing volleyball and women's basketball, respectively, at Boise State and Montana, and Audrey Hofer, who plays volleyball at Montana State. All were studs, all were seniors, all were larger than life. The Bruins would end the season perfect, making their winning streak 71 matches and winning a third straight Class AA title.

It was a high-pressure environment for an underclassman, one filled with anxiety. Then there was schoolwork and the drive for classroom excellence, and then there was the reputation she was building as a standout softball player. It's a lot to carry. One of the solutions she considered: stepping away from softball, relieving the pressure a bit. She spent time with the school counselor, started seeing a therapist, began taking anxiety medication.

Years, decades ago, she would have felt pressure to keep it quiet, deal with it, get over it on her own. At least bottle it up, be stronger. And if she needed help, certainly don't admit to it. Those things are now all out in the open, no longer taboo. "She had some struggles going on for sure. It was a weird time for her that kind of sparked that anxiety," says Aspen. "She wants other athletes to know it happens and that there is help out there and that tomorrow can be different."

She took a break from softball that winter, struggled to find the motivation to begin spring practices but used the resources she was provided to rediscover her love of the sport and of competition. She didn't miss a game that season. "She came out of it and is not afraid to talk about her story," says Aspen. "Now that helps me as a coach. There is definitely a burnout mode. Recognizing that in our athletes is huge to give them a different pathway of what they need at that time."

As she continued getting better, a new stress was added to her life: college recruiting. Playing for the Grizzlies was Plan A. Playing somewhere else was Plan B. Not playing collegiately, well, she didn't want to even think about that.

She was new to this and didn't know how to read the tells, the signals that coaches were dropping. Were they interested? Were they not? How is a girl to know? At one tournament she bumped into future Grizzly teammate Grace Haegele, who asked Herndon how it was going. Herndon told her that Meuchel had given Herndon her phone number. Oh, that's a good sign, Haegele told her. "That's when everything chilled out. My stress level went down from there."

Then the offer to Montana arrived. Then the tears, for all of it, from seven months old to high school anxieties to wondering if this would ever happen. In the end, she had what the Grizzlies wanted.

"When she came to our camps, you just saw an untapped talent," says Meuchel. "I don't even know if she has a ceiling. She is such a coachable kid. She'll look you directly in the eye, she pays attention, she wants to grow, she wants to learn. There were so many intriguing things about her."

All that did was remove one stress, college recruiting, and throw another in its place. Now she was the Division I-bound softball pitcher and every batter she would face going forward wanted to use her to make their own statement, to measure themselves. She entered her senior year at Capital injured from a non-softball setback and never did make it all the way to the end of the season. She had to shut it down early.

"It was a little bit weird for her. She wasn't her full potential at the time. On top of that, people wanted a piece. That was a hard pill to swallow, not being able to go out on top or try to go out on top," says Aspen. "That was the hardest thing for her and for me to see her go through, not being able to end her high school story."

She made her collegiate debut in the fall exhibition season, at least she thinks she did. "I was feeling jacked," she says, "ready for it, then when I got out there I kind of blacked out. This is real! Just the fact I got to accomplish what was a dream of my younger self and pitching for the first time since I was injured, I thought it was pretty cool. Once I snapped out of it, I was able to go."

(Note to Nyeala: You made three appearances in eight games in the fall, throwing 3 2/3 innings. You allowed four hits, walked three, struck out five. Standard first-year-player stuff. You know, in case you blacked out for the rest of it as well.)

"Ny throws the ball hard," says Meuchel, who calls her pitcher "Ny," while Aspen calls her "Nay." Should you make your way to Grizzly Softball Field this spring, just know they are all calling for the same person. Herndon is fine with all of it. After all this, you think she's going to fret over something as inconsequential as that?

"When she is on, she can get it to break really well. She is a competitor. She is a great teammate and willing to put anything she can in for her team. She finds ways to make outs. As we see her ability to pound the zone grow, we'll see her success and the success of our team grow with that."

It's all bonus now for Aspen, who for the last 17 years was warned of end points, that her daughter and her heart could do A but probably not B, then B but probably not C, then C but probably not D. She is deep into the alphabet now, humming along with a full, healthy heart, no limits in sight.

"We were told for a long time that they were not sure how much physical conditioning she would be able to handle, how much longer she'll be able to be an athlete or to what level she'll ever be able to play at full potential," says Aspen.

"To get to Montana, to see her commit, put on that uniform and kind of have it all flash in my head, it was a miracle. You always think, okay, what's the next step, what's the next bridge we're going to have to cross that she might not be able to do? With a lifetime of things holding us back, then not having those anymore, it was so amazing that I can't even put into words. At the same time, so scary."

It's a mother's natural setting, particularly one with her history. She sees a big, strong college freshman but can't help but see that seven-month-old and wonder if she is truly okay, if that heart can do what it's being asked of. It's a burden a mom will carry for life, her own scars, never to fully heal.

It's another success story for Dr. Dennis Ruggerie, who says none of what he does has ever felt like work. He has bad days, of course, as all pediatric cardiologists are going to have. Part and parcel to the career choice, an inherent burden.

Then this seven-month-old comes into your life, she fights off death, grows in size and in character from the experience, becomes Nyeala Herndon, Division I athlete, future early-childhood educator, role model.

"We've tried to emphasize to Nyeala that she has a very special story but she also has a very normal heart," says Ruggerie. "I think she is going to take that gift and go forward and do some very good things for her community, her family. She is going to make her mother very proud."

Too late, Dr. Ruggerie. She already has.

Granted, for some it's more transactional, Montana the best or most appealing option of the many on the table, the end result – college softball – always the understood or expected destination, with only the particulars – the school, the scholarship offer – to figure out. Those are fun but don't produce quite the same feels.

And then there are some, like the day she sat down with Aspen and Nyeala Herndon, that just hit differently, layers of feelings to unpack and try to handle, Aspen never getting the chance to play college softball because of the era and growing up in small-town Montana, Nyeala falling for the Grizzlies that day at home in Helena when Montana played in the NCAA tournament in 2017 on ESPN, now realizing the long-held hope of playing for her home-state team.

It was the best. "We had a real special visit with her," says Meuchel. "We talked about what we had here for Ny, knowing how special it would be for her to be in Missoula and close to home, close to her family and be able to compete for a state she really loves. As we talked through things, you could see how special this opportunity would be, one she didn't know would be available for her. Pretty special moment."

Then the Herndons shared with Meuchel the deeper reason for all the tears, beyond the more typical ones, of hard work paying off, of a childhood dream of playing college softball coming true. They told Meuchel a life story, of facing death, of overcoming the odds that predicted this would never happen, that Nyeala would never be here. A story that answers the question: Do you really think pitching in a tight game with runners on second and third is going to faze Nyeala Herndon?

It started with a low-grade fever, the inability to keep food down when she was seven months old. Must be teething, Aspen was told when she called in with her concerns. But bring her in if you think it's serious. It was. A stethoscope found no sounds coming from her left lung, nothing functioning, nothing coming in, nothing going out. And just like that, Nyeala Herndon was in a fight for her life, and she was on the ropes, on the way to losing by knockout, blindsided. She would have had no idea what was happening, why everyone was suddenly in crises mode.

Dr. Dennis Ruggerie, who spoke about Herndon's case for this article with consent from the family, happened to be in Helena that day, at an outreach clinic from his normal post in Great Falls, he the state's first-ever full-time pediatric cardiologist living and working in Montana when he was hired in 1989.

He was contacted, told the particulars. How serious was it? He dropped everything he was doing and scheduled to do, and immediately ordered a helicopter transport to fly from Great Falls to Helena to pick Herndon and her mom up and take them back to Great Falls, knowing the saving of even a few minutes might make a life-and-death difference. "It was very clear she was critically ill and we needed to get her to Great Falls to our pediatric ICU," Ruggerie says.

The antagonist was a non-threatening-sounding cold virus, though Herndon had just overcome a case of RSV (respiratory syncytial virus). This new adversary found a weak link, her heart, and went into attack mode. All out, full on. Herndon was intubated and put on a breathing machine, IVs were quickly inserted, medicines pumped into her bloodstream to give her body a fighting chance at making it one more hour, one more hour, one more hour, life going, in half a day, from routine to perilous, skipping all the steps in between, from healthy to just holding on. "Her heart was working at a level that was incompatible with survival without our critical-care technology and drug-therapy support," says Ruggerie. "Her heart was failing." She was suffering from myocarditis.

A normal heart operates at 55-65 percent efficiency, its pump filling with blood, then contracting and ejecting blood into the arteries, 55 to 65 percent of the available blood getting discharged. That's normal. Herndon's number was dropping by the hour, like a countdown clock ending in the worst-case scenario, the virus winning its fight against the heart, the battle for Herndon's life. Forties, thirties, twenties, teens, single digits. "She was probably less than five to seven percent. They are all bad numbers when it's under 12 percent. Those are incompatible with survival," Ruggerie says.

Aspen had had six months of bliss at home with her firstborn, fretting over the usual things, the temperature of the fluid in the feeding bottle, the contents of her daughter's crib, the right toys to stimulate proper development skills. Now, when every motherly instinct screamed at her to do something, to fight for her daughter, she was left as a spectator as nurses and doctors did things to and for Nyeala that her mom will never be able to unsee.

The tiny patient was sedated to mask the pain of the horrors being inflicted upon her fragile body. Nothing exists for a parent in that moment. Sleep won't come. Fatigue and emotions that have run dry result in a downward spiral until a parent is in a haze, almost watching the proceedings like it's an out-of-body experience, their real person no longer capable of tapping into an empty reservoir of strength and energy.

"Aspen saw us doing things to her baby that she couldn't comprehend," says Ruggerie. "It was an absolute nightmare, but she was very strong and listened very well. She trusted us. We needed her to trust us." Herndon was stabilized but still teetering on that fine edge between life and death, the longer she was there, the longer she was needing all-out support, the less likely the end result was going to be a good one.

Ruggerie got into pediatric cardiology, a profession not for the weak of (ahem) heart, not because of some divine calling but because he didn't understand it, "and that bothered me," he says. "I understood adult cardiology well, general medicine issues well and had very good training in pediatrics. I just had a hard time understanding congenital heart disease, so I thought I would take the challenge."

He graduated from the Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine in 1981, did an internship at Grandview Hospital in Dayton, then a residency at Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, then a fellowship at the same hospital.

I have a friend who is an emergency room doctor in Duluth, Minn. He says he's come to be able to handle the arrival of death in his presence for anyone over the age of 30 or 40 by accepting that they were able to experience most of the great "firsts" in life if they chose to do so. The first time falling in love. First job. First birth of a child. It's how he can sleep at night after a particularly rough shift. But how does a guy handle a career in pediatric cardiology, when every patient has never had a first in life, when every patient he sees is at their most vulnerable in life?

"It takes different people to do different kinds of work," Ruggerie says. "I always wanted to be a person who others came to for help, whatever comes through the front door. I wanted to be that guy and part of the team of people who were ready to meet the challenge, stabilize kids, treat kids, help them get better, whether the child was born to survive or had a fatal injury."

A child comes into his life and the full spectrum of end results is at play, an early death and grieving parents to the first step toward recovery and a life that may span decades and decades and decades, and who knows what that person might accomplish? It's a big burden to carry, being the one who willingly takes on that load.

"You learn to compartmentalize the sad outcomes and stay in the action by following your assessment skills, your algorithms, your pathways, making sure you do the same thing over and over and over again, no matter how sick the child is," he says. "You keep thinking your way through it and try to keep your emotions in a box. If you're leading a team, you need to present a strong position to keep the other team members focused and strong so we don't miss an opportunity to actually save a child."

Who better to have watching over your child when life – and everything you thought it was going to be, for you, for your daughter – is unraveling before your eyes? Nyeala Herndon's heart was failing. The virus was still on the attack, doing more damage, some of it potentially irreversible, by the hour. Her heart was dying. With everything going against her, she remained in the best of hands.

The entire thing becomes a chess match for Ruggerie, he says, of thinking two, three, four moves ahead. He met with Aspen every two hours, to fill her in on the status of her daughter, what her options were, one of them, at the very worst of moments, to prepare to be with her daughter as she passed away, the virus doing so much damage to Nyeala's seven-month-old heart that even Ruggerie and his team couldn't overcome it. Another, a long shot, a life flight to Salt Lake City and Primary Children's Hospital to get on the list for a heart transplant, something that had to happen now, right now, because another day of worsening and weakening and Herndon would never have been able to survive the stress of the flight. Big moments, little time to decide.

It became a numbers game. "The outcome expectations were that Nyeala had one-third chance of dying, one-third chance of surviving with her heart ultimately returning to normal, though that may take years, and one-third chance of surviving with a damaged heart and long-term heart failure," Ruggerie says. It was as dark as it could get for the family, knowing the idea of a transplant offered a small light of hope but knowing the wait, if it came to it, would almost certainly come to an end before a heart, just the right size, healthy enough to survive, became available.

She's here, about to play her freshman season of Division I softball, so you know how it ended up. Within days of arriving in Salt Lake, her heart, with plenty of medical help, started to win the fight, started to get the upper-hand on the virus, though the effects of the battle would be long-lasting, her heart ravaged, a pugilist surviving but showing the scars, asked to do what it wasn't designed to.

She got off ICU support, then after three months was taken off the transplant list, then, after four months at Primary's Children's Hospital, was allowed to return to Great Falls, where Aspen and Nyeala lived in the local Ronald McDonald House for easier access to her multiple appointments each week. She was on the road to recovery but it was a long one and they were only just starting their journey.

At age 5, her number of medications dropped from five to two, clinic visits tapered off to monthly, to every six months, to yearly. Eventually she was weaned off all medications and last summer she underwent a cardiac MRI that revealed, for the first time since she was six months old, an absolutely normal heart, a plain old boring and most beautiful heart, just doing its thing. The scarring was gone and there had been a regrowth of the damaged heart cells. It only took 17 years to get there.

"We had a lot of good luck, she got a lot of good care and we had a lot of good prayers," says Ruggerie, whose clinic is located at 2510 Bobcat Way but gave his best to a future Grizzly anyway. "She has become a quiet, pleasant, smart young lady with a mother who is very dedicated to her. I think she had it in her to begin with because her mother does. It's a great story any way you want to look at it."

So, yeah, some visits between Meuchel and a prospective player and a parent, when an offer is made to play Division I softball for the Grizzlies, just mean a little bit more. "It's a story we don't like to rethink but when we do and think about everything we've been through as a family, it's very humbling," says Aspen. "To see her success despite everything she's had to fight has been amazing."

Call it life's payback, a special gift presented to those who are born prematurely or who go through myocarditis or in some other way have to fight for life before they're even aware they're doing so. They take away a little bit of something special from the experience, something they can apply to the rest of their lives. NICU nurses swear by it, a fighting spirit acquired for life.

"I don't know if it's because of what she went through, but when she has to rise to the occasion, she rises," says Aspen. "She's just always had that in her. I've seen that academically in her, I've seen it at home with her. She's always been that kid. Then when it's done, she goes back to her quiet, reserved self."

Of course, there were some lingering effects of the ordeal, both physical (for Nyeala) and mental (for Aspen), mom filling with worry every time her daughter took off running down the street. After all, how could a heart that had gone through what Nyeala's had be up for supporting a fully active lifestyle?

Thank goodness she was at first interested in art. No stress there! Same for dance and gymnastics. Same for tee-ball, all low on the exertion level. We're all good, right mom? Then her friends started playing softball, and Nyeala wanted to join. Uh-oh. Mom kept worrying about limitations and what her daughter's sporting ceiling would ultimately be based on her heart and its restrictions. Nyeala wanted to break through them, her spirit begging her heart to keep up – let's go! – mom both scared and amazed at the same time at what was happening, the envelop being pushed when no one could say for sure what was too far or what the end point might be.

Aspen had grown up watching her own mom play slow-pitch softball in Townsend, finally joined in when she was 14. "Loved it, loved it," she says. She kept playing it in Helena, bringing her daughter, then daughters, along.

Coaching? A 10-year-old interested in pitching? She tapped every resource she could in Helena, watched YouTube videos of Cat Osterman and Jenny Finch, took Nyeala to private lessons, absorbed all the teachings herself, learning enough that today she has a side gig, along with being a college and career counselor at Capital High, as the pitching coach at Carroll College.

"Trying to make sure we were doing it safely and getting her to where she could be successful at it, whatever level that was at the time," says Aspen, who began coaching her daughters' teams and who perhaps unintentionally developed a Division I pitcher by intentionally not handing the starting job to her daughter just because she was the coach's daughter and wanted to pitch. You want it? Go out and earn it. Become so good that I have no other choice but to use you as my ace. "I'm a lot harder on them than other kids," she says. "You've got to go put in the work if you want to be our starting pitcher. I'm not just going to give you the position." Can you feel it? Mom growing stronger as her daughter's heart did the same thing, mom coming out of her uneasiness, mom gently pushing now? You can do it.

She became a pretty big deal, Nyeala did, at least in Montana. That was fine, but people saw something more in her, greater than simply pitching high school ball in the state. It was time spent with Morgan Ray, who starred at Frenchtown High before pitching at Ohio State, that convinced the family that being a big fish in a small pond didn't need to be Herndon's end game or future. She had the stuff to pitch collegiately.

Herndon was playing at a tournament in Oklahoma City when she got an email from someone with the Washington Ladyhawks, who have one of the best travel-ball organizations in the Northwest. And would Herndon like to join them? It would be her ticket to the larger world of age-group softball.

It's just what she needed. Pitches on the outer half of the plate, which worked for her in Montana, were ripped for base hits the other way. Pitches when she missed by an inch or two weren't fouled off, they were smoked for extra bases. Even when she was perfect with her spin and placement, she could still get hit hard. She had to get better. She had just seen if firsthand.

"It was eye-opening that there was another level that players in Montana don't really know about," Herndon says. "It was eye-opening to see the difference, their knowledge of the game, their pitch selection and their mechanics. It was more college-level than I was used to."

Nature, those experiences she went through, perhaps some nurture, has led her to have an ideal composition for a pitcher, someone who has the equanimity to realize that it's just softball blended together with that rise-to-the-occasion toughness. A blend of competitiveness with a life-is-bigger-than-softball mindset. And it works.

At a 12U tournament, facing, if they remember correctly, Kynzie Mohl on the other team, Herndon pitched a silver-platter special, and Mohl did what she's always been doing to those pitches. She sent it screaming over the fence. "She lays this fat pitch across the plate and she just sends it yard," recalls Aspen. It was the kind of home run that would have sent most pitchers that age asking to be repositioned to the outfield. "Nay turned to the dugout, looked at us and shrugged her shoulders," says her mom. "She got the ball back and struck out the next one. She has always not let it get to her on the mound."

She doesn't have it all figured out, no matter how rosy and uplifting her story may read. She wants you to know that. And she wants you and athletes who come behind her to know that it's okay to not only not have it figured out but to admit it. And to seek help.

When she was a sophomore, she made the varsity volleyball team at Capital High, playing alongside Paige and Dani Bartsch, who are playing volleyball and women's basketball, respectively, at Boise State and Montana, and Audrey Hofer, who plays volleyball at Montana State. All were studs, all were seniors, all were larger than life. The Bruins would end the season perfect, making their winning streak 71 matches and winning a third straight Class AA title.

It was a high-pressure environment for an underclassman, one filled with anxiety. Then there was schoolwork and the drive for classroom excellence, and then there was the reputation she was building as a standout softball player. It's a lot to carry. One of the solutions she considered: stepping away from softball, relieving the pressure a bit. She spent time with the school counselor, started seeing a therapist, began taking anxiety medication.

Years, decades ago, she would have felt pressure to keep it quiet, deal with it, get over it on her own. At least bottle it up, be stronger. And if she needed help, certainly don't admit to it. Those things are now all out in the open, no longer taboo. "She had some struggles going on for sure. It was a weird time for her that kind of sparked that anxiety," says Aspen. "She wants other athletes to know it happens and that there is help out there and that tomorrow can be different."

She took a break from softball that winter, struggled to find the motivation to begin spring practices but used the resources she was provided to rediscover her love of the sport and of competition. She didn't miss a game that season. "She came out of it and is not afraid to talk about her story," says Aspen. "Now that helps me as a coach. There is definitely a burnout mode. Recognizing that in our athletes is huge to give them a different pathway of what they need at that time."

As she continued getting better, a new stress was added to her life: college recruiting. Playing for the Grizzlies was Plan A. Playing somewhere else was Plan B. Not playing collegiately, well, she didn't want to even think about that.

She was new to this and didn't know how to read the tells, the signals that coaches were dropping. Were they interested? Were they not? How is a girl to know? At one tournament she bumped into future Grizzly teammate Grace Haegele, who asked Herndon how it was going. Herndon told her that Meuchel had given Herndon her phone number. Oh, that's a good sign, Haegele told her. "That's when everything chilled out. My stress level went down from there."

Then the offer to Montana arrived. Then the tears, for all of it, from seven months old to high school anxieties to wondering if this would ever happen. In the end, she had what the Grizzlies wanted.

"When she came to our camps, you just saw an untapped talent," says Meuchel. "I don't even know if she has a ceiling. She is such a coachable kid. She'll look you directly in the eye, she pays attention, she wants to grow, she wants to learn. There were so many intriguing things about her."

All that did was remove one stress, college recruiting, and throw another in its place. Now she was the Division I-bound softball pitcher and every batter she would face going forward wanted to use her to make their own statement, to measure themselves. She entered her senior year at Capital injured from a non-softball setback and never did make it all the way to the end of the season. She had to shut it down early.

"It was a little bit weird for her. She wasn't her full potential at the time. On top of that, people wanted a piece. That was a hard pill to swallow, not being able to go out on top or try to go out on top," says Aspen. "That was the hardest thing for her and for me to see her go through, not being able to end her high school story."

She made her collegiate debut in the fall exhibition season, at least she thinks she did. "I was feeling jacked," she says, "ready for it, then when I got out there I kind of blacked out. This is real! Just the fact I got to accomplish what was a dream of my younger self and pitching for the first time since I was injured, I thought it was pretty cool. Once I snapped out of it, I was able to go."

(Note to Nyeala: You made three appearances in eight games in the fall, throwing 3 2/3 innings. You allowed four hits, walked three, struck out five. Standard first-year-player stuff. You know, in case you blacked out for the rest of it as well.)

"Ny throws the ball hard," says Meuchel, who calls her pitcher "Ny," while Aspen calls her "Nay." Should you make your way to Grizzly Softball Field this spring, just know they are all calling for the same person. Herndon is fine with all of it. After all this, you think she's going to fret over something as inconsequential as that?

"When she is on, she can get it to break really well. She is a competitor. She is a great teammate and willing to put anything she can in for her team. She finds ways to make outs. As we see her ability to pound the zone grow, we'll see her success and the success of our team grow with that."

It's all bonus now for Aspen, who for the last 17 years was warned of end points, that her daughter and her heart could do A but probably not B, then B but probably not C, then C but probably not D. She is deep into the alphabet now, humming along with a full, healthy heart, no limits in sight.

"We were told for a long time that they were not sure how much physical conditioning she would be able to handle, how much longer she'll be able to be an athlete or to what level she'll ever be able to play at full potential," says Aspen.

"To get to Montana, to see her commit, put on that uniform and kind of have it all flash in my head, it was a miracle. You always think, okay, what's the next step, what's the next bridge we're going to have to cross that she might not be able to do? With a lifetime of things holding us back, then not having those anymore, it was so amazing that I can't even put into words. At the same time, so scary."

It's a mother's natural setting, particularly one with her history. She sees a big, strong college freshman but can't help but see that seven-month-old and wonder if she is truly okay, if that heart can do what it's being asked of. It's a burden a mom will carry for life, her own scars, never to fully heal.

It's another success story for Dr. Dennis Ruggerie, who says none of what he does has ever felt like work. He has bad days, of course, as all pediatric cardiologists are going to have. Part and parcel to the career choice, an inherent burden.

Then this seven-month-old comes into your life, she fights off death, grows in size and in character from the experience, becomes Nyeala Herndon, Division I athlete, future early-childhood educator, role model.

"We've tried to emphasize to Nyeala that she has a very special story but she also has a very normal heart," says Ruggerie. "I think she is going to take that gift and go forward and do some very good things for her community, her family. She is going to make her mother very proud."

Too late, Dr. Ruggerie. She already has.

Players Mentioned

Griz Football at Montana State Bus Departure - 12/19/25

Saturday, December 20

Griz Football at Montana State Juicer - 12/18/25

Saturday, December 20

Griz Football vs. South Dakota (Defense) - 12/13/25

Saturday, December 20

1995 National Champions: 30-Year Anniversary

Wednesday, December 17